March 1st Movement

| March 1st Movement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Korean independence movement | |||

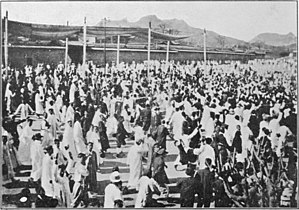

A march during one of the protests in Seoul (1919) | |||

| Date | March 1, 1919 – months afterwards | ||

| Location |

| ||

| Caused by | Ideals of self-determination, discontent with colonial rule, and theories that former Emperor Gojong had been poisoned by Japan | ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | Nonviolent resistance | ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Concessions |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 7,509 (Korean estimate)[1] | ||

| Arrested | 46,948 (Korean estimate)[1] | ||

The March 1st Movement[a] was a series of protests against Japanese colonial rule that were held throughout Korea and internationally by the Korean diaspora beginning on March 1, 1919. In South Korea, the movement is remembered as a significant event of not only the Korean independence movement, but in all of Korean history.

The protests began with a reading of the Korean Declaration of Independence in Tapgol Park, Seoul. The movement grew and spread rapidly; one estimate puts the number of protests at over 2,000, with over 2,000,000 participants total. Protests continued for months afterwards. Despite the peaceful nature of the protest, they they were frequently violently suppressed. One Korean estimate in 1920 claimed 7,509 deaths and 46,948 arrests. Japanese authorities reported much lower numbers, although there were instances where authorities were observed destroying evidence, such as during the Jeamni massacre, where Japanese soldiers burnt down a church to destroy the bodies of around 20 to 30 Korean civilians they had lured into the church before killing.[2]

While the movement did not result in Korea's imminent liberation, it had a number of significant effects. It invigorated the Korean independence movement and resulted in the creation of the Korean Provisional Government. In addition, the Japanese colonial government began granting limited cultural freedoms to Koreans under a series of policies that have since been dubbed "cultural rule". Furthermore, the movement went on to inspire other movements abroad, including the Chinese May Fourth Movement and Indian satyagraha protests.[3]

The anniversary of the protest has been celebrated each year since 1919, although this was largely done in secret in Korea until its liberation in 1945. In South Korea, it is a national holiday. The North Korean government, however, does not evaluate the movement's significance similarly, and promotes writings about the event that seek to emphasize the role of the ruling Kim family in the protests.[4]

Background[edit]

In 1910, Japan formally annexed Korea. Japanese rule was initially especially tight. Japan took control over Korea's economy, and began a process of Japanization: forced cultural assimilation. Resistance was violently suppressed, and freedom of speech and press were tightly controlled.[1][5] Months before the protests, a number of events occurred that heightened Korean discontent and stirred independence sentiment.[1]

Fourteen Points[edit]

After the conclusion of World War I in 1918, United States President Woodrow Wilson published his Fourteen Points, which included the right of national self-determination.[6][1] Koreans who learned of this were inspired and interpreted this as signaling support for their independence movement. Their sympathy to the United States and to the Allies greatly increased, when previously they had reportedly disliked the alliance because Japan was a member of it.[7]

Korean-American independence activists such as Syngman Rhee, Min Chan-ho, and Jeong Han-gyeong attempted to send a Korean representative to the 1919–1920 Paris Peace Conference, but the United States denied them permission to go.[1][8] Some Koreans, including Kim Kyu-sik, managed to eventually attend the conference by traveling along with Chinese delegates and by using pseudonyms. Chinese leaders, hoping to embarrass Japan, attempted to put a discussion of Korea's sovereignty on the agenda, but did not succeed.[9]

According to the interpretation of several scholars, Wilson had intended for the statement to apply mostly the former colonies of the defeated Central Powers, which Japan was not a part of.[1][10] Regardless, the colonial government suppressed discussion of the Fourteen Points, even reportedly going so far as to ban a foreign film from being screened in Korea because it had images of President Wilson.[11]

Gojong's death and poisoning theories[edit]

Just days after the beginning of the Paris Peace Conference, Gojong, the former emperor of Korea, died on January 21, 1919. Japan reported that Gojong had died from natural causes, but he had reportedly been healthy just until his death. Koreans widely suspected that Japan had poisoned him;[1][12] this was thought especially credible because previous attempts had been made on his life.[13]

The outrage at the possibility that Gojong had been murdered has since been evaluated as having a critical impact on the timing of, and even the occurrence of the March 1st Movement.[12][14]

February 8 Declaration of Independence[edit]

By the mid-1910s, several hundred Korean students were studying in Japan as part of Japan's cultural assimilation efforts.[15][16] While there, they were exposed to and developed a variety of ideas, which they discussed and debated. Of particular interest to them were ideas from the West, particularly liberal democracy, which they received in part via the Japanese Taishō Democracy movement and Wilson's Fourteen Points.[16]

By early 1919, their ideas coalesced, and they also became angered by the rebuffing of the Korean representatives, by the brutality of Japanese rule, and by the possibility that Gojong had been poisoned. On Feburary 8, 600 students of the Korean Young People's Independence Organization (조선청년독립단; 朝鮮靑年獨立團) proclaimed and publicly distributed a declaration of independence, which they sent to not only the Japanese government, but also to the Paris Peace Conference and to representatives of various countries.[1][17] The students were arrested en masse by Japanese authorities, although news of their act reached Korea.[18]

Organization[edit]

In late 1918, leaders of the native Korean religion Cheondoism, including Kwǒn Tong-chin and O Se-chang, reached a consensus that nonviolent resistance and turning international public opinion against Japan would be effective in advocating for Korea's independence.[1][19] They also agreed that they needed assistance from other major groups in Korea.[1]

They dispatched representatives to negotiate and secure the cooperation of major politicians and groups in Korea. Some negotiations were strained and took months, and they were initially so disheartened that they reportedly even considered abandoning their plan. However, the events of January and February 1919 caused a spike in pro-independence activism, and they quickly secured a number of significant alliances. They gained the support of several former government officials from the Korean Empire, although they were rebuffed by Joseon-era politicians Park Yung-hyo and Han Kyu-sŏl. They also secured alliances from major Christian and Buddhist groups, as well as from several student organizations.[1]

They decided to schedule their protest for the same day as Gojong's public funeral, in order to capitalize on the significant amount of people congregating in Seoul.[12][14] The funeral was initially scheduled for March 3. However, it was rescheduled to March 1 for religious reasons.[1][clarification needed]

From February 25 to 27, representatives from these various groups held a series of secret meetings in Seoul, during which they produced and signed the Korean Declaration of Independence. From 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. on February 27, they printed 21,000 copies of the declaration at the printing facilities of Posǒngsa, a publisher affiliated with Cheondoism. On the morning of the 28th, they distributed these copies around the peninsula, to members of the Korean diaspora, to U.S. President Wilson, and to participants in the Paris Peace Conference. That day, they held a final meeting and reviewed their plans for the protests.[1]

They initially planned to start the protest at Tapgol Park in Seoul, where they'd invite thousands of students to hear the reading of the declaration. However, worries that they were putting the students in danger caused them to change the starting location to the restaurant Taehwagwan in Insa-dong. This eventually led to a miscommunication, where the students were invited to the park regardless.[1]

Beginning[edit]

Around noon on March 1, 1919, twenty-nine of the thirty-three signers of the declaration gathered in Taehwagwan in Seoul in preparation to start the protest. However, the Korean restaurant owner An Sun-hwan (안순환; 安淳煥) secretly reported the meeting to the Japanese Government-General of Chōsen, and around eighty Japanese military police officers rushed over and arrested the signers.[1]

Meanwhile, around 4,000 to 5,000 students had assembled at Tapgol Park after hearing there was going to be an announcement made there. They waited for the announcement to start, unaware that most of the protest's organizers had been arrested.[1]

Around 2 p.m., an unidentified young man rose up before the crowd and began reading the Korean Declaration of Independence aloud. Near the end of the document's reading, cheers of "long live Korean independence" (대한독립 만세) erupted continually from the crowd, and they filed out onto the main street Jongno for a public march.[1]

By the time the marchers reached the gate Daehanmun of the former royal palace Deoksugung, their numbers had swelled to the tens of thousands. From there, a number of splinter groups marched in different directions throughout the city. News of the protests spread rapidly in Seoul, and marching and public demonstations continued for many hours afterwards.[1]

These protestors were reportedly consistently peaceful, but were met with violent repression by Japanese authorities, which resulted in deaths and arrests.[1]

Spread[edit]

That same day, similar protests were held in other cities in Korea, including in Pyongyang, Chinnamp'o, Anju, and Wonsan. Despite Japanese repression of information, news of the protest in Seoul reached these cities quickly, as they were connected to Seoul via the Gyeongui and Gyeongwon railway lines.[1] On March 2, more protests were held in Kaesong and Keiki-dō (Gyeonggi Province). On March 3, more were held in Yesan and Chūseinan-dō (South Chungcheong Province). Protests continued to spread in this fashion, until by March 19, all thirteen provinces of Korea had hosted protests. On March 21, Jeju Island held their first protest.[1]

Various locations often hosted multiple protests for weeks afterwards. Seoul hosted thirteen and Haeju hosted eight.[1] Numerous small villages hosted three or four protests.[1] For example, Hoengseong County held a series of protests from March 27 to mid-April.[20] Protests often coincided with market days, and were often held at government offices.[1]

It is impossible to know the precise number of protests that occurred in Korea, as well as their sizes. One estimate puts the number of protests at over 2,000, with over 2,000,000 participants total. The protests were broadly supported across economic and religious spectrums. A significant number of merchants, noblemen, literati, kisaeng, laborers, monks, Christians, Cheondoists, Buddhists, students, and farmers supported the movement.[1]

Character of the protests[edit]

The character of each protest differed, possibly due to the influence of local culture and religion. In some regions, Christians played a more significant role in organizing protests, and in others Cheondoists were more significant.[1] The scholar Kim Jin-bong argued that Christians played a larger role in regions with more developed transportation, and Cheondoists in regions with less developed transportation.[1]

North Hamgyong Province was the last province to join the protests. Kim Jin-bong characterized its protests as being less intense, and attributed this to transportation being less developed there, as well as security being tighter due to it being on the border with both Russia and China.[1] In Chūseihoku-dō (North Chungcheong Province) and Chūseinan-dō, some radical groups attacked and destroyed Japanese government offices and police stations. Zenrahoku-dō (North Jeolla Province) had protests that have been characterized as less intense than others. This has been attributed to the region being relatively depleted after having previously heavily participated in the 1894–1895 Donghak Peasant Revolution and subsequent righteous army conflicts. In this province and in Zenranan-dō (South Jeolla Province), students often played a significant role in protests.[1]

Korean diaspora protests[edit]

Manchuria[edit]

On March 7, Koreans in Manchuria learned of the movement. They held a significant protest in Longjing on March 13. Estimates of the number of protestors vary, although some put the number of protestors at around 20,000 to 30,000.[21][22][1] This was around 10% of the total Korean population of the region at the time.[23]: 1:34 One person, who had sent her son to the protest, later recalled what she had heard of it:[24][b]

I heard that a large crowd of people gathered from all over to hear the news. After the noon bell finished ringing, a large flag celebrating Korea's independence was unfurled. Everyone raised their own flags and shouted "long live Korean independence". The flag blocked the sun, and the shouting echoed like thunder. When the Japanese authorities saw this, their faces turned ashen.

Japanese authorities pressured the Chinese warlord Zhang Zuolin into suppressing the protest. This resulted in around 17 to 19 deaths.[25][26][1] Like in Korea, they continued to hold protests for weeks afterwards. The region of Jiandao (Gando in Korean) hosted around 54 protests by mid-May.[24]

Russian Empire[edit]

Koreans in Russia also learned of the protests, and began organizing their own. In Ussuriysk, a protest was held and suppressed on March 17. The Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan had been part of the Allies of World War I, and had signed agreements to suppress the Korean independence movement. Inspired by the Ussuriysk protest, the Koreans of the enclave Shinhanchon in Vladivostok launched their own that same day, which was also suppressed. They launched another the following day.[27]

United States[edit]

Koreans in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States held the First Korean Congress and a public rally in support of Korean independence.[1]

Suppression[edit]

The Japanese Government-General of Chōsen was reportedly unaware that the protest would happen, and was surprised by the scale and intensity of them. They rushed to recruit people from various backgrounds, including security guards at railroads, to stop the protests. The government-general received more military police and police officers from Japan, as well as two more army divisions. They equipped these groups with lethal weapons and distributed them around Korea.[1]

In numerous instances, Japanese authories killed unarmed and peaceful protestors. Japanese authorities conducted organized bayonet charges in some instances, which killed and injuried many. During an intense raid on Suwon and Anseong, Japanese authorities reportedly burnt 276 private homes down, killed 29, and arrested around 2,000 people. A significant number of people were tortured and executed.[1]

During the raid on Suwon and Anseong, in one infamous instance now known as the Jeamni massacre, a Japanese lieutenant lured 20 to 30[2] Korean civilians into a church, opened fire on them, then burned the church down to hide the evidence of the killings. The Canadian missionary Frank Schofield photographed the aftermath of these raids, and wrote articles that he sent for publication to the international press.[1]

- Several of Schofield's photographs

An article in the San Francisco Examiner reported that students in Pyongyang were stripped naked, tied to crosses, and publicly flogged. According to an article in The Washington Post, in one instance, a girl had her hand cut off by a Japanese soldier because she was holding a copy of the declaration. However, she reportedly switched to holding the document in her other hand, and continued to protest.[28]

Statistics[edit]

The statistics around the suppression of the March 1st Movement are not known with certainty, and are a subject of controversy.[1]

The history book The Bloody History of the Korean Independence Movement (한국독립운동지혈사; 韓國獨立運動之血史) by Korean scholar Park Eun-sik reports the following statistics:

| Region | # protests | # participants | # deaths | # injuries | # arrests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gyeonggi | 297 | 665,900 | 1,472 | 3,124 | 4,680 |

| Hwanghae | 115 | 92,670 | 238 | 414 | 4,218 |

| Pyongan | 315 | 514,670 | 2,042 | 3,665 | 11,610 |

| Hamgyong | 101 | 59,850 | 135 | 667 | 6,215 |

| Gangwon | 57 | 99,510 | 144 | 645 | 1,360 |

| Chungcheong | 156 | 120,850 | 590 | 1,116 | 5,233 |

| Jeolla | 222 | 294,800 | 384 | 767 | 2,900 |

| Gyeongsang | 223 | 154,498 | 2,470 | 5,295 | 1,085 |

| Overseas | 51 | 48,700 | 34 | 157 | 5 |

| Total | 1,542 | 2,023,098 | 7,509 | 15,961 | 46,948 |

Park's book was published in 1920,[29] so it is possible that the numbers are higher, as Japanese authorities continued pursuing and arresting the protestors for years afterwards.[1]

Japanese sources differ on the statistics. From March 1 to April 11, Japanese officials reported 553 people killed, and more than 12,000 arrested. They said that 8 policemen and military were killed, and 158 wounded. As punishment, some of the arrested demonstrators were executed in public.[30]

Yu Gwan-sun[edit]

Yu Gwan-sun, a 16-year-old participant in the protests, has since become a symbol of March 1st Movement, and is now remembered in South Korea as a martyr. On the first day of the protests, Yu, then a student at Ewha Haktang, participated in the protest in Seoul. On March 5, she participated in another protest at Namdaemun in Seoul and was arrested. Missionaries from her school negotiated her release. She then returned to her hometown of Cheonan, albeit with a smuggled copy of the Declaration of Independence. From there, she went from village to village, spreading the news of the protests and encouraging people to organize their own. On April 1, 3,000 protestors gathered in Cheonan. The Japanese military police opened fire on the protestors and killed 19; among the dead were Yu's parents.[31]

Yu was arrested and detained at Seodaemun Prison in Seoul. She was repeatedly beaten and tortured, but unrepentantly continued to advocate for Korea's independence. She eventually died of her injuries on September 28, 1920.[31]

Japanese reactions and response[edit]

The movement was widely seen as an embarrassment to the colonial government, although opinions on the movement's causes and how to prevent future protests differed. Journalist and colonial government official Hosoi Hajima saw the March 1st Movement as emblematic of Japan's failure to act as a proper "big brother". Others agreed that the protest was serious, but still salvageable.[32]

Cultural rule[edit]

The colonial government began significant reform efforts. Many of these efforts have been grouped under the name "cultural rule" (Japanese: 文化政治; bunka seiji). These policies allowed several limited cultural freedoms and programs for Koreans. This included permission for several Korean newspapers to be founded, including The Dong-a Ilbo and The Chosun Ilbo,[1] as well as the establishment of institutions like the Chōsen Art Exhibition[33] and the Government-General of Chōsen Library.[34] In addition, while the colonial government had previously been more consistently dismissive towards Korean culture, it began conceding that Korea had some unique traditions worthy of protection and development.[1]

The scholar Kim Jin-bong evaluates these policy changes as being largely cosmetic and intended to appease Koreans and international observers. Throughout the period of cultural rule, Japan continued violently suppressing the Korean independence movement.[1] By the late 1930s, many of these concessions were retracted, and Japan began enforcing assimilation with greater intensity.[5]

Suppression of information and misinformation campaign[edit]

Japan attempted to stop the news from leaving the peninsula. Major Japanese newspapers made some initial reports on the event; they almost uniformly downplayed its scale and did not cover it as the main story. Eventually, they ceased reporting on it.[28] However, the English-language newspapers The Japan Chronicle and The Japan Advertiser published a number of articles that were about the violent suppression of the movement, with the latter covering the events of the Jeamni massacre.[1]

Foreign witnesses in Korea played a significant role in documenting, photographing, and communicating information about the event abroad. The first communication about the event to leave the Japanese Empire was in English and went to Shanghai. This led to the first international article on the movement being published there on March 4.[35]

News of the protests first reached the United States on March 10, via a cablegram sent by Korean independence activists in Shanghai to San Francisco. The story was quickly picked up by other American papers. However, the veracity of the story was initially held in doubt. In the March 11 issue of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, judge John Albert Matthewman, who had previously volunteered for the Red Cross in Korea, stated that he felt that Koreans in Shanghai had fabricated the story. He felt this way because he had observed Japan being so repressive, that such a large-scale protest was functionally impossible to execute.[28]

In response to the increasing numbers of foreign inquiries, various Japanese bodies released public statements that either denied that protests had occurred in Korea at all, downplayed the scale of them, or claimed that they had been fully suppressed much earlier than in reality. There are records of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs lodging official complaints to the United States and Germany for publishing what it deemed to be rumors about the protests, with requests to stop their publication.[28] Furthermore, Japan promoted narratives that Koreans were uncivilized and incapable of self-governance; Western journalists who were sympathetic to Japan (for example, one who was born in Japan) published this narrative in various newspapers internationally, including in articles published by The New York Times and by the Los Angeles Times.[28]

Foreign newspapers eventually became consistently skeptical of Japan's narratives, and some reported that Japan was attempting to suppress the news and spread misinformation about the protests.[28]

International reactions[edit]

Within days, numerous countries around the world reported on the event and often wrote critically of its violent suppression.[36][1] Western countries often focused on the plight of Korean Christians.[36] However, foreign governments did not openly oppose Japan's rule over Korea, nor did they condemn the violence applied in suppressing the protests. This was largely due to each government determining that forwarding their policy goals with Japan outweighed offering support to Korea.[1][10]

United States[edit]

In April 1919, the U.S. State Department told their ambassador to Japan that "the consulate [in Seoul] should be extremely careful not to encourage any belief that the United States will assist the Korean nationalists in carrying out their plans and that it should not do anything which may cause Japanese authorities to suspect [the] American Government sympathizes with the Korean nationalist movement."[38] On July 15, Republican senators Miles Poindexter and George W. Norris opposed the ratification of the articles of the League of Nations, and cited Korea as an example of a nation the organization had failed to aid.[1] Many American journalists and an American Presbyterian church organization condemned the violent suppression of the protests.[1]

Ultimately, the U.S. did officially not condemn Japan's suppression of the movement or support Korea's independence.[1][10]

China[edit]

While the Chinese government did not openly advocate for Korea's independence, it offered support in a number of other ways.[1][28] The Republic Daily News, which was strongly aligned with the Chinese government, covered the protests on a daily basis for some time, praising the protestors and criticizing their suppression.[3][28] Prominent Chinese intellectual Chen Duxiu, in his magazine The Weekly Review (每週評論), praised the protests and advocated for Chinese people to follow the Korean example. Student journalists of Peking University similarly wrote favorably of the protests.[3] These sentiments were echoed by English-language newspapers in China, including the Peking Daily News and Peking and Tientsin Times.[1]

United Kingdom[edit]

In the early 1920s, British members of parliament Arthur Hayday and Thomas Walter Grundy mentioned the issue of Korea and asked what could be done for it. In addition, a society that advocated for Korea's independence formed in both the U.K. and France called The Friends of Korea (French: Les Amis de la Coree). None of these efforts resulted in significant action.[1]

Russia[edit]

Vladimir Lenin, then engaged in the Russian Revolution, capitalized on resistance movements such as the March 1st Movement in order to link these movements with the cause of the Bolsheviks. After the Soviet Union assumed control over territories with significant Korean populations in the Russian Far East, it allowed and sometimes encouraged Koreans to openly express support for the Korean independence movement.[1] The Soviet linking of communism to the Korean independence movement was criticized by the American newspaper The Sun.[1]

Mexico[edit]

Mexican newspapers began publishing on the movement on March 13, and widely condemned Japan's actions.[36] The Korean community in Mexico launched a fundraising campaign in response to the movement, and sent the raised funds to Korean independence activists in Shanghai. Despite the community living in significant poverty, one estimate claims the Koreans there donated an average of 20% of their income to the independence movement.[39]

Impact and aftermath[edit]

While the movement did not secure Korea's liberation, it had a number of significant effects for Korea and a number of other countries.[1][3]

Amidst the violent repression of the protests and the hunt for its participants and leaders, numerous Koreans fled the peninsula. A number of them congregated in Shanghai, and in April 1919, they founded the Korean Provisional Government (KPG). This government is now considered the predecessor to the modern government of South Korea, and holds an important place in the independence movement and in South Korean identity.[1]

Other independence movements[edit]

Several weeks later, organizers of the May Fourth Movement in China such as Fu Ssu-nien cited the March 1st Movement as one of their inspirations.[3] That protest has since been evaluated as a critical moment in modern Chinese history.[40][41]

Indian independence activist Mahatma Gandhi read of the peaceful protests while in South Africa. He reportedly decided to return to India soon afterwards and launch the non-cooperation movement.[3]

In the U.S.-occupied Philippines, university students in Manila held a pro-independence protest in June 1919, and cited the March 1st Movement as inspiration.[3]

In British-occupied Egypt, students of Cairo University held a pro-independence protest amidst the 1919 Egyptian revolution, and cited the March 1st Movement as an inspiration.[3]

Commemorations[edit]

South Korea[edit]

On May 24, 1949, South Korea designated March 1st as a national holiday.

In 2018, President Moon Jae-in's administration established the Commission on the Centennial Anniversary of March 1st Independence Movement and the Korean Provisional Government (KPG) to celebrate these occasions.[42] The KPG was the government-in-exile of Korea during the Japanese occupation, and a predecessor of the current government. North Korea refused to participate in the joint project of the anniversary due to "scheduling issues".[43] The commission ceased its operation in June 2020.

Seoul Metropolitan Government stated the March 1st movement as "the catalyst movement of democracy and the republic for Korean people."[44]

North Korea[edit]

In the North, the day is remembered as "The People's Uprising Day" (인민 봉기일), and taught as the day that Kim Il Sung's family took the lead of the independence movement. Kim would have been around eight years old around 1919. It is commemorated as a relatively minor holiday, with mostly central and few local celebrations. The events are geared towards inciting anti-American and anti-Japanese sentiment.[4][45]

The epicenter of the movement is taught as being Pyongyang instead of Seoul, and the contributions of figures who became influential in the later South Korean government are downplayed. The 33 national representatives who are considered to have led the movement in the South are replaced by Kim Hyong-jik, Kim's father. Those 33 representatives are instead described as having surrendered immediately after reading their declaration. Furthermore, eight-year-old Kim is described as leading a march for some 30 li from the Mangyongdae neighborhood of Pyongyang to the Potong Gate, also in Pyongyang.[45]

While scholars in both the South and North are in relative consensus that the movement was doomed to fail (at least in the short term), North Korean textbooks argue that the movement failed because of bourgeois interference and the lack of a central proletariat revolutionary party to lead it.[45]

Other regions[edit]

A number of other places with significant Korean diaspora populations have commemorated the anniversary of the March 1st Movement at a variety of points in time.

The Korean enclave Shinhanchon in Vladivostok, Russia commemorated the anniversary of the movement each year from 1920.[46]

Korean-Mexicans in the city of Mérida celebrated the anniversary of the movement with public events in recent years. Some celebrations have included reenactments of the reading of the declaration and public marches.[47][48]

Apology[edit]

In August 2015, Yukio Hatoyama, who had previously served as Prime Minister of Japan for nine months, visited Seodaemun Prison, where many protestors had been held, and apologized on his knees for how the prisoners had been treated.[31]

See also[edit]

- History of Korea

- May Fourth Movement in China

- Yu Gwan-sun

- Refrain club

- National Liberation Day of Korea

Notes[edit]

- ^ Korean: 3·1 운동; this name is sometimes transliterated as the Sam-il Movement, where "sam" and "il" are the Korean reading for 3 and 1. Alternate name Manse Movement (Korean: 만세운동; Hanja: 萬歲運動; lit. Ten-thousand Year Movement)

- ^ 저녁 때 들으니 사방에서 인사들이 소식을 듣고 모여 인산인해를 이루었다고 한다. 정오 종소리에 맞춰 용정 부근 서전대야에 큰 조선독립 깃발을 세우고 사람마다 태극기를 들고 조선독립만세를 부르며 독립을 선언했다. 깃발은 해를 가리고 함성은 우레와 같았다. 이를 본 왜인의 얼굴색이 잿빛으로 변했다.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc 김, 진봉, "3·1운동 (三一運動)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-04-29

- ^ a b 김, 진봉, "수원 제암리 참변 (水原 堤岩里 慘變)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-04-30

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shin, Yong-ha (February 27, 2009). "Why Did Mao, Nehru and Tagore Applaud the March First Movement?". The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2009-06-27 – via Korea Focus.

- ^ a b Kim, Hyeon-gyeong (1 March 1997). "In North Korea, March 1st is distortedly taught as being caused by the Kim Il-sung family". MBC News. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ a b 정, 진석; 최, 진우. "신문 (新聞)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ Neuhaus, Dolf-Alexander (2017). ""Awakening Asia": Korean Student Activists in Japan, The Asia Kunglun, and Asian Solidarity, 1910–1923". Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review. 6 (2): 608–638. doi:10.1353/ach.2017.0021. S2CID 148778883.

- ^ Manela 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Chang, Roberta (2003). The Koreans in Hawai'i: A Pictorial History, 1903–2003. University of Hawaii Press, p. 100.

- ^ Manela 2007, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Hart-Landsberg, Martin (1998). Korea: Division, Reunification, & U.S. Foreign Policy. Monthly Review Press. p. 30.

- ^ Manela 2007, pp. 129–130.

- ^ a b c Manela 2007, p. 132.

- ^ "Did you know that ...(22) The coffee plot". The Korea Times. 2011-09-09. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ a b Wells 1989, p. 7.

- ^ Manela 2007, p. 125.

- ^ a b Wells 1989, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Hae-yeon, Kim (2023-02-23). "[Newsmaker] Handwritten English translation of Feb. 8 Declaration of Independence found after 104 years". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ 박, 성수, "2·8독립선언서 (二八獨立宣言書)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-04-29

- ^ Wells 1989, p. 14.

- ^ 김, 영인 (2019-01-03). "횡성 4·1만세운동 공원 호국 성지화 사업 추진". Yonhap News Agency (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ 김, 광재, "3·13반일시위운동 (三·一三反日示威運動)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-04-03

- ^ 안, 상경 (2022-03-11). "[아! 만주⑰] 용정 3.13반일의사릉: 만주에서 울린 그 날의 함성을 기억하다". 월드코리안뉴스 (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ 영상한국사 I 67 3월 13일, 간도 용정에서 대규모 만세시위가 벌어지다. Retrieved 2024-04-03 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ a b 안, 상경 (2022-03-11). "[아! 만주⑰] 용정 3.13반일의사릉: 만주에서 울린 그 날의 함성을 기억하다". 월드코리안뉴스 (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ 김, 광재, "3·13반일시위운동 (三·一三反日示威運動)", 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture] (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-04-03

- ^ 윤, 병석 (2008). 북간도지역 한인 민족운동 (in Korean). 독립기념관 한국독립운동사연구소. p. 173. ISBN 9788993026658.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ 안, 영배 (2020-01-18). "두만강 건너간 한인들이 세운 '신한촌'… 해외 독립운동 상징으로". The Dong-a Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 김, 상훈 (2019-02-14). "[외신속 3·1 운동] ① 그 날 그 함성…통제·조작의 '프레임' 뚫고 세계로". 연합뉴스 (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ 송, 병기, "한국독립운동지혈사 (韓國獨立運動之血史)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-04-29

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, and Walthall, Anne (1947). East Asia : a cultural, social, and political history (Third ed.). Boston. ISBN 9781133606475. OCLC 811729581.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Kang, Inyoung (2018-03-29). "Overlooked No More: Yu Gwan-sun, a Korean Independence Activist Who Defied Japanese Rule". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Caprio, Mark E. (2011). "Marketing Assimilation: The Press and the Formation of the Japanese-Korean Colonial Relationship". The Journal of Korean Studies. 16 (1): 16–17. doi:10.1353/jks.2011.0006. ISSN 0731-1613. JSTOR 41490268.

- ^ 이, 경성, "조선미술전람회 (朝鮮美術展覽會)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-03-12

- ^ 강, 주진, "국립중앙도서관 (國立中央圖書館)", Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 2024-03-12

- ^ 김, 상훈 (2019-02-14). "[외신속 3·1 운동] ① 그 날 그 함성…통제·조작의 '프레임' 뚫고 세계로". 연합뉴스 (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ a b c 국, 기헌 (2019-02-24). "[외신속 3·1 운동] ⑬ 중남미 언론 "코레아, 해방 원한다"…日 대량학살 고발(끝)". Yonhap News Agency (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Peffer, N. (1920). "Korea's Rebellion: the part played by Christians". Scribners Magazine. 67 (5): 513.

- ^ United States Policy Regarding Korea, Part I: 1834–1941. US Department of State. pp. 35–36.

- ^ 남, 문희 (2021-10-03). "쿠바의 한인, 우리가 알지 못했던 독립운동가들". 시사IN (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Wasserstrom, Jeffrey N. (2019-05-04). "Opinion | May Fourth, the Day That Changed China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "May Fourth Movement". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2024-03-22. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "March 1st Independence Movement and Korean Provisional Government >Memories & Gratitude>March 1st Independence Movement>March 1st Independence Movement". Archived from the original on 2020-06-16. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- ^ Gibson, Jenna (Mar 1, 2019). "Korea Commemorates 100th Anniversary of March 1st Independence Protests".

- ^ "서울 볼거리 구경하기 – 서울에 아름다움을 느껴보세요". Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Han, Yeong-jin (28 February 2006). "Eight-year-old boy Kim Il-sung gathered the independence movement and travelled 30 li". Daily NK. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ 안, 영배 (2020-01-18). "두만강 건너간 한인들이 세운 '신한촌'… 해외 독립운동 상징으로". The Dong-a Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ "메리다 3.1운동 100주년 만세운동 재현 상세보기|대사관 보도자료주멕시코 대한민국 대사관". overseas.mofa.go.kr. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "한복 입고 3·1절 기념행사 참석한 멕시코 한인후손들". 재외동포신문 (in Korean). 2024-03-04. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

Sources[edit]

- Manela, Erez (2007-07-23). The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803915-0.

- Wells, Kenneth M. (1989). "Background to the March First Movement: Koreans in Japan, 1905—1919". Korean Studies. 13: 5–21. ISSN 0145-840X.

Further reading[edit]

- Baldwin, Frank (1972). The March First Movement: Korean Challenge and Japanese Response. Columbia University Press.

- Cumings, Bruce (1997). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W.N. Norton and Company.

- Han, Woo-keun (1988). The History of Korea. U of Hawaii Press.

- Hart, Dennis. "Remembering the nation: construction of the March First movement in North and South Korean history textbooks" Review of Korean Studies (Seoul) 4, no. 1 (June 2001) pp. 35–59, historiography

- Kim, Juhea (2021). Beasts of a Little Land. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 117–131. ISBN 9780063093577.

- Ko, Seung Kyun. The March First Movement: A Study of the Rise of Korean Nationalism under the Japanese Colonialism Koreana Quarterly: A Korean Affairs Review (Seoul) 14, no. 1–2 (1972) pp. 14–33.

- Ku, Dae-yeol. Korea Under Colonialism: The March First Movement and Anglo-Japanese Relations (Royal Asiatic Society, Seoul, 1985) online review

- Kwon, Tae-eok. "Imperial Japan's 'civilization' rule in the 1910s and Korean sentiments: the causes of the national-scale dissemination of the March First Movement" Journal of Northeast Asian History 15#1 (Win 2018) pp. 113–142.

- Lee, Timothy S. "A political factor in the rise of Protestantism in Korea: Protestantism and the 1919 March First Movement." Church History 69.1 (2000): 116–142. online

- Palmer, Brandon. "The March First Movement in America: The Campaign to Win American Support." Korea Journal (2020), 60#4 pp 194–216

- Shin, Michael (2018). Korean national identity under Japanese colonial rule: Yi Gwangsu and the March First Movement of 1919. Routledge.