Bethlehem, Georgia

Bethlehem, Georgia | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| Motto: "The little town under the star" | |

Location in Barrow County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 33°56′11″N 83°42′38″W / 33.93639°N 83.71056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Barrow |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.302 sq mi (6.0052 km2) |

| • Land | 2.3 sq mi (6.00 km2) |

| • Water | 0.002 sq mi (0.0052 km2) |

| Elevation | 860 ft (262 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 715 |

| • Density | 310.9/sq mi (119.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 30620[2] |

| Area codes | 770; 404; 678 |

| FIPS code | 13-07612[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0331150[4] |

| Website | www |

Bethlehem is a town in Barrow County in the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 715. The major employer in town is Harrison Poultry, which is the largest non-government employer in Barrow County.

The town was named after a local church, Bethlehem Methodist Church, and has a strong Christmas theme, with many of the street names being references to the nativity of Jesus, such as Mary, Joseph, and Manger. After the introduction of a 1967 stamp in Bethlehem, the town became known as a popular location for sending mail from during the holidays, as the post office sends letters marked "from Bethlehem."

History[edit]

The land that Bethlehem and the surrounding Barrow County occupies was originally occupied by Cherokee and Creek tribes. European settlers first arrived in the area in 1786.[5] The Bethlehem Methodist Church was established in 1796 in what would later become Bethlehem.[6] The church opened an adjacent camp ground that was used between 1851 and 1894 which was used as a troop mobilization center during the American Civil War.[5] The Confederate States Army's 16th Georgia Regiment was formed at the camp ground, and the grounds were used as a refugee camp during the war.[7] During the Reconstruction era onwards the camp ground was used for various religious services.[5][7] A Christian revival meeting was taking place on August 31, 1886, when shockwaves from the 1886 Charleston earthquake were felt at an estimated MMI intensity of 6.[8][9] The camp ground is now the current location of the Bethlehem Methodist Church, which was built in 1949.[5]

The area was informally established as the community of Bethlehem in December 1883[7] as a stop along the Belmont – Monroe line[10] of the Gainesville, Jefferson and Southern Railroad. The stop was named after the local Bethlehem Methodist Church.[11] The church itself was named after the ancient town of Bethlehem, identified in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke as the birthplace of Jesus. The railway line was removed in 1946.[12] Bethlehem was incorporated as a town in 1902 by an act of the Georgia General Assembly "under the name and style of the town of Bethlehem".[13] At the time of its incorporation it was part of Walton County, but later became part of the newly formed Barrow County in 1914, which was created using land previously belonging to the nearby Gwinnett, Jackson, and Walton counties.[5]

In 1986 a 13-year-old Bethlehem Elementary School student made national headlines[14][15] when he stabbed his principal Murray Kennedy to death with a nail file.[16] Because the white principal was killed by a black student, the incident stoked fears of racial conflict in the community, which were addressed by local black and white leaders in the community.[17] The case drew the attention of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference who helped contribute to the student's defense fund.[18] It also drew the attention of the Ku Klux Klan; 65 members of the Ku Klux Klan held a rally in front of the Winder, Georgia courthouse in protest of the murder.[19][20] Despite the involvement of the KKK, fears of racial tension in the community itself quickly died out.[21] After being charged as an adult,[22] the student was sentenced to 15 years after pleading guilty to voluntary manslaughter.[23]

Geography[edit]

Bethlehem is located in southern Barrow County, 4 miles (6.4 km) south of Winder, the county seat. The town is 24.1 miles (38.8 km) west of Athens, Georgia,[24] and 49.1 miles (79.0 km) east of Atlanta.[25] According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 2.3 square miles (6.0 km2), with approximately 0.002 square miles (0.0052 km2) of water.[26] The land in and around Bethlehem forms a watershed that flows into the Apalachee River and Marburg Creek, which itself flows into the Apalachee River.[27] Around 76.4% of the land in Bethlehem is used for agriculture or forestry, followed by 14.8% for residential use.[28]: 4–6

Climate[edit]

The climate of Bethlehem, as with most of the southeastern United States, is humid subtropical (Cfa) according to the Köppen classification,[29] with four seasons including hot, humid summers and cool winters. July is generally the warmest month of the year with an average high of around 90 °F (32 °C). The coldest month is January which has an average high of around 53 °F (12 °C).[30]

Bethlehem receives rainfall distributed evenly throughout the year as typical of southeastern U.S. cities, with March on average having the highest average precipitation at 5.12 inches (130 mm), and May typically being the driest month with 3.17 inches (81 mm).[30]

| Climate data for Bethlehem, Georgia (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 53 (12) |

58 (14) |

66 (19) |

74 (23) |

81 (27) |

88 (31) |

90 (32) |

89 (32) |

83 (28) |

74 (23) |

65 (18) |

55 (13) |

73 (23) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 31 (−1) |

33 (1) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

67 (19) |

67 (19) |

60 (16) |

49 (9) |

40 (4) |

33 (1) |

49 (9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.66 (118) |

4.46 (113) |

5.12 (130) |

3.57 (91) |

3.17 (81) |

4.26 (108) |

4.07 (103) |

3.95 (100) |

4.10 (104) |

3.67 (93) |

4.01 (102) |

3.72 (94) |

48.76 (1,237) |

| Source: US Climate Data[30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 209 | — | |

| 1920 | 246 | 17.7% | |

| 1930 | 209 | −15.0% | |

| 1940 | 242 | 15.8% | |

| 1950 | 240 | −0.8% | |

| 1960 | 297 | 23.8% | |

| 1970 | 304 | 2.4% | |

| 1980 | 281 | −7.6% | |

| 1990 | 348 | 23.8% | |

| 2000 | 716 | 105.7% | |

| 2010 | 601 | −16.1% | |

| 2020 | 715 | 19.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

As of the census of 2020, there were 715 people, 341 households, and 241 families residing in the town. The population density was 310.9 inhabitants per square mile (120.0/km2). There were 341 housing units at an average density of 148.3 per square mile (57.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 64.11% White, 9% African American, 0% Native American, 0.67% Asian, 0.48% Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, 13.63% from other races, and 12.09% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 49.97% of the population.[1]

There were 341 households, out of which 42.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.2% were married couples living together, 11.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.3% were non-families. 27.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 21.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.06 and the average family size was 3.99.[1]

In the town, the population was spread out, with 32% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 25.5% from 25 to 44, 16% from 45 to 64, and 17.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 118.9 males.[1] The median income for a household in the town was $53,281, and the median income for a family was $59,050. The median income for a non-family household was $38,043. Males had a median income of $30,417 versus $16,250 for females. The per capita income for the town was $21,969. About 2.49% of the population were below the poverty line.[1]

Economy[edit]

Bethlehem, as with the rest of Barrow County, has a sales tax of 7%, which is composed of the 4% Georgia state sales tax and a 3% local tax.[32] According to the U.S. Census's American Community Survey 2020 5-year estimate, 57.3% of Bethlehem's population that are 16 years or older are in the labor force. Of these, around 56.26% of the total population being employed, and 1.38% of the total population being unemployed.[1] The largest employer in the town is Harrison Poultry, which opened in Bethlehem in 1958 and is the largest non-government employer in Barrow County with around 1,000 employees.[33]

Holiday postal tradition[edit]

Bethlehem's post office is popular during the holiday season for sending cards and letters,[34][35] as mail sent from there will feature Bethlehem's cancellation mark and cachet, so that holiday mail sent will state that it is sent with "Greetings from Bethlehem."[36] This special Bethlehem cancellation mark is made with a stamping machine called a flier canceler. Bethlehem's flier canceler is more than 100 years old and is the only one still in use by the U.S. Postal Service.[34] The Bethlehem post office's special cachet features the Three Wise Men and the Star of Bethlehem.[35]

Traveling to Bethlehem to send holiday mail is a holiday tradition for visitors of the town and the Bethlehem post office sends hundreds of thousands of pieces of mail during each Christmas season.[34][36] The post office also has hand-stamps that customers can use to stamp "Christmas Greetings from Bethlehem" on their letters and cards before being sent.[37]

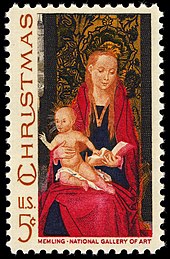

The tradition began in 1967, when the United States Postal Service debuted a special Christmas stamp at the Bethlehem post office with a ceremony that included then-governor of Georgia Lester Maddox and Assistant U.S. Postmaster General Richard J. Murphy.[35][38] While it was the sixth Christmas stamp produced by the US Postal Service, it was the first Christmas stamp to be produced in the larger commemorative size, which is almost twice the size of the previous Christmas stamp.[39] The stamp was a reproduction of Hans Memling's Madonna and Child with Angels.[40] Despite only regularly employing the postmaster and one other part-time employee in a town that at the time had around 350 people,[41] this stamp was requested by so many people that the town's postmaster hired 43 temporary workers to handle the increased workload[42] caused by people sending in their mail to Bethlehem to be re-sent out with the Christmas stamp's first-day-of-issue date of November 6.[38] The Bethlehem post office ultimately sent out around 500,000 cards and letters during the 1967 Christmas season.[35]

Arts and culture[edit]

The town operates a library inside City Hall as part of the Piedmont Regional Library System.[43] Bethlehem has no designated historic districts.[28]: 4–2 The nearby Kilgore Mill Covered Bridge and Mill Site (also known as Bethlehem Bridge[44]) was built in 1874[5] and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, and crosses over the Apalachee River, which serves as the boundary between Barrow and Walton counties.[45] Bethlehem hosts an annual nativity pageant[5] during each Christmas season at the town square on Christmas Avenue, below the illuminated large star which represents the Star of Bethlehem.[8] The original star was put in place in 1951 and measured 15 feet (4.6 m) across,[46] and was replaced in 2009 with a star measuring 12 feet (3.7 m) due to excessive rust and nonfunctioning lights on the original.[47]

Parks and recreation[edit]

The town has one designated park, the R. Harold Harrison Community Playground, which includes a playground, walking trail, and covered pavilion.[48] The closest state park is Fort Yargo State Park, located approximately 7 miles (11 km) north of Bethlehem in Winder.[49]

Government[edit]

When the town was incorporated in 1902 it was established that the town would operate as a civil township under a mayor and five councilmen, each with a term of one year.[13] This government style was reaffirmed by an act passed during a 2004 session of the Georgia General Assembly, which added a town clerk to the council.[50]

In the United States House of Representatives, Bethlehem is part of Georgia's 10th congressional district.[51] For representation in the state government, the town is part of the Georgia State Senate's 47th district, and the 116th district for the Georgia House of Representatives.[52]

Education[edit]

Public education for students in Bethlehem is administrated by Barrow County Schools. Bethlehem is part of the Apalachee cluster and is served by Bethlehem Elementary School, Haymon-Morris Middle School, and Apalachee High School.[53] High school students in Bethlehem are also able to apply to attend two college preparatory schools in Barrow County, Sims Academy of Innovation & Technology[54] or the Barrow Arts & Sciences Academy.[55] Snodon Preparatory School was located in Bethlehem until its closure in 2019, and served students from grades 9–12.[56][57] Following its closure, students in Bethlehem have the option to attend a charter school in Athens known as Foothills Education Charter High School on lottery basis.[58] Bethlehem Christian Academy is a private school located in Bethlehem that serves Pre-K through 12th grade.[59]

Media[edit]

As part of the North Georgia area, Bethlehem's primary network-affiliated television stations are WXIA-TV (NBC), WANF (CBS), WSB-TV (ABC), and WAGA-TV (Fox).[60] WGTV is the local station of the statewide Georgia Public Television network and is a PBS member station.[61] Bethlehem is served by the weekly newspaper Barrow News Journal,[62] which also serves as Barrow County's legal organ (also called a "newspaper of public record").[63] AM radio station WJBB operates their main studio out of Bethlehem.[64]

Infrastructure[edit]

Transportation[edit]

Monroe Highway (SR 11) runs through Bethlehem in a north-to-south direction, while intersecting with SR 316 (US 29) inside the town limits, which runs from west-to-east through the town.[65] SR 316 also intersects with SR 81 inside Bethlehem, which also runs north-to-south through the town.[66] Many, but not all,[67] of the street names in Bethlehem are references to the nativity of Jesus and the Bible,[67][68] including such streets as Angel Street, Joseph Street, Manger Avenue, and Star Street.[69]

The town lacks any form of public transportation and has limited sidewalks for pedestrian use.[28]: 4–4 The nearest airport is the Barrow County Airport in the city of Winder, a small public use airport with two asphalt runways 7 miles (11 km) from Bethlehem.[70] The closest major airports are Athens–Ben Epps Airport, which is 27 miles (43 km) from Bethlehem, and Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, which is 58 miles (93 km) away.[70]

Utilities[edit]

Electricity in the town is provided by Georgia Power,[71] while water utilities are provided by the nearby City of Winder.[72] Unlike the rest of Barrow County which sources its water from the Bear Creek reservoir in Jackson County,[73] Bethlehem and the City of Winder sources its water from three local sources: the Mulberry River, City Pond, and Fort Yargo Lake.[74] Bethlehem contracts directly with a private trash hauling company to handle disposal of solid waste as a free service to residents.[75][71] In 2019 the mayor of Bethlehem, Sandy McNabb, cited the lack of sewer infrastructure as "the primary reason for the lack of growth in Bethlehem."[69]

Healthcare[edit]

Bethlehem currently has no hospitals inside its town limits. The closest hospital is Northeast Georgia Health System Barrow, also known as NGHS Barrow, which is located in Winder 6 miles (9.7 km) north of downtown Bethlehem.[76] Piedmont Walton is located in Monroe 10.5 miles (16.9 km) south of downtown Bethlehem.[77] In May 2022 the Barrow County Planning Commission approved the construction of a new Northeast Georgia Medical Center facility in Bethlehem.[78]

Notable people[edit]

- Jody Hice, the U.S. representative for Georgia's 10th congressional district since 2015.[79]

- Howard W. Odum, American sociologist and author.[80]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "ZIP Code™ by City and State". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bethlehem History". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. December 22, 1996. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Kaemmerlen, Cathy J. (2019). Georgia Place-Names From Jot-em-Down to Doctortown. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing Inc. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4396-6753-8. OCLC 1111473053.

- ^ a b c "Georgia's Bethlehem Exemplifies Christ". The Atlanta Constitution. December 24, 1936. pp. 1, 2. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Callaway, Chip (December 20, 1970). "Bethlehem, Ga.: Where Christmas Comes Alive". The Atlanta Journal and Constitution. p. 16-B. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lux Mitigation and Planning Corp. "Barrow County Hazard Mitigation Plan Update 2019 – 2024" (PDF). Barrow County. p. 111. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Fergusson, Jim (February 18, 2022). "Georgia Railroads – SL 234 Passenger Stations and Stops" (PDF). The Branch Line Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins. Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-915430-00-2. OCLC 1482211.

- ^ Boring, Bill (December 8, 1947). "Christmas Spirit Stirs in Georgia's Bethlehem". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Georgia, General Assembly (1903). Acts and Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia (1902 ed.). Atlanta, Georgia: The Franklin Printing and Publishing Company. p. 344.

- ^ "Boy, 13, Charged in Slaying Ga. Principal With Pencil". Jet. December 15, 1986. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Student charged with stabbing elementary school principal". UPI. November 20, 1986. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "13-Year-Old Called To Principal's Office, Stabs Him To Death". Associated Press. November 20, 1986. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Turner, Renee D. (November 24, 1986). "Barrow leaders call for calm, unity after principal's slaying". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. B-2. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Walston, Charles (February 2, 1987). "SCLC: Ruling on teen biased". The Atlanta Constitution. p. E-1. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Klan Protests Slaying Of Principal in Georgia". The New York Times. February 22, 1987. p. 32. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Klan protests defense efforts for teen facing murder charge". Gainesville Sun. February 22, 1987. p. 8A. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Earle, Joe (November 25, 1986). "Tensions easing in Barrow after principal's death". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 17-A. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Earle, Joe (February 1, 1987). "Boy to face adult trial in murder case". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Booker, Lorri Denise (April 17, 1989). "Principals take aim at school violence". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. 3-E. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Google (December 28, 2022). "Athens, Georgia to Bethlehem, Georgia" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ Google (December 28, 2022). "Atlanta, Georgia to Bethlehem, Georgia" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Bethlehem town, Georgia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ "Revised TMDL Implementation Plan HUC 0307010108 – Marburg Creek and Upper Apalachee River" (PDF). georgia.gov. August 1, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c MACTEC Engineering and Consulting, Inc. (June 7, 2007). Barrow County Comprehensive Plan 2007–2027 (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Interactive United States Köppen Climate Classification Map". Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Climate Bethlehem – Georgia". Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Sales Tax Rates – General". Georgia Department of Revenue. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Lameiras, Maria (July 8, 2021). "Harrison Foundation pledges $1M to UGA Poultry Science". University of Georgia. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c Bridges, Kathy (December 18, 2018). "Barrow County's Bethlehem gets its postmarks ready for Christmas". The Gainesville Times. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Kent, Peter J. (December 11, 1997). "Following Yonder Star: For Christmas card senders, the destination is Bethlehem". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Johnston, Andy (December 13, 2011). "Little town goes all out for holiday". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jones, Andrea (December 21, 2001). "Annual stampede: Postmark from Bethlehem is seasonal symbol for crowds". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Stamp Ceremony ends in Bethlehem". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. November 7, 1967. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Yule Stamp for 1967 Honors Bethlehem, Ga". Idaho Statesman. November 4, 1967. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1966 and 1967 Traditional Christmas Issues". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Yule Mail is Booming in Bethlehem, Ga". Belleville News-Democrat. December 13, 1967. p. 11. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ McCarthy, Rebecca (December 24, 2004). "Bethlehem is one happy stamper". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. J3. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved July 15, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bethlehem services". Town of Bethlehem, GA. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form". National Park Service. April 14, 1975. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ "Register of Historic Places". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ Cuddihy, Kevin (2005). Christmas's most wanted: the top 10 book of Kris Kringles, merry jingles, and holiday cheer. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-61234-036-4. OCLC 758984915.

- ^ Blackburn, Ryan (November 16, 2009). "New Christmas star to shine over Bethlehem". Gwinnett Daily Post. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ "Parks & Playgrounds in Barrow County". Barrow County Family Connection. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Fort Yargo – State Park Winder". Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Town of Bethlehem – New Charter" (PDF). Town of Bethlehem, GA. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "My Congressional District". census.gov. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Find Your Legislators". openstates.org. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "School Maps – Elementary, Middle, and High". Barrow County Schools. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Apply now for early college courses". Sims Academy of Innovation and Technology. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "About Barrow Arts & Sciences Academy". Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Snodon Preparatory School (Closed 2016)". Public School Review. Archived from the original on December 29, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- ^ "Snodon transition plans underway". Barrow News-Journal. August 27, 2019. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Enrollment Information". Foothills Education Charter High School. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Our History". Bethlehem Christian Academy. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Bethlehem TV Stations and Networks List". American Towns. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "WGTV". Georgia Public Broadcasting. May 24, 2010. Archived from the original on May 25, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ "Barrow News Journal". Barrow County Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Barrow County Georgia Local News". Barrow County, Georgia. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "AM Station WJBB – FCC Public Inspection File". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Swanepoel, Sharon (August 5, 2020). "New bridge on SR 11 over Apalachee River now open". Monroe Local. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Huppertz, Karen (August 14, 2020). "Interchange at Ga. 316 and Ga. 81 opens Aug. 24 in Bethlehem". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "List of Streets in Bethlehem, Barrow County, Georgia, United States". geographic.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ "Bethlehem". georgia.gov. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Hunter, Lauren (October 13, 2019). "Bethlehem: A small town with Christmas spirit". accessWDUN. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Nearest airport to Bethlehem, Georgia". travelmath. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "Newcomer's Guide to Bethlehem" (PDF). www.bethlehemga.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Scott (November 27, 2019). "Barrow County, City of Winder remain apart on two SDS issues". Barrow News-Journal. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Barrow County Georgia Water Department". Barrow County, Georgia. Archived from the original on December 19, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Annual Water Quality Report". Winder Water Works. May 1, 2008. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Regional Solid Waste Management Plan 2021–2031". Northeast Georgia Regional Commission. p. 6-3. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Jim (December 31, 2016). "Northeast Georgia Health System acquires Barrow Regional Medical Center". Athens Banner-Herald. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Hensley, Ellie (April 3, 2018). "Clearview Regional becomes Piedmont Walton Hospital". Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Ervin, Morgan (May 25, 2022). "Builders of new NGMC facility at 316 corridor seek variance from county". Barrow News-Journal. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ "Hice". The Hill. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Special Interest". The Atlanta Constitution. April 8, 1945. p. 6-B. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

External links[edit]

- Town of Bethlehem official website

- Bethlehem United Methodist Church historical marker