Cato Street Conspiracy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

| Cato Street Conspiracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Revolutions during the 1820s | |||

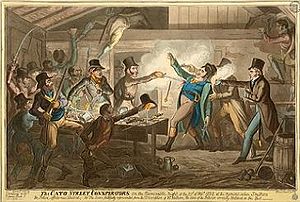

The arrest of the Cato Street conspirators. | |||

| Date | 22-23 February 1820 | ||

| Location | Cato Street, London | ||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals | Overthrow of the Government | ||

| Methods | |||

| Resulted in | Conspiracy foiled | ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 1 police officer | ||

| Arrested | 13 conspirators | ||

| Charged | 5 executed 5 exiled | ||

The Cato Street Conspiracy was a plot to murder all the British cabinet ministers and the Prime Minister Lord Liverpool in 1820. The name comes from the meeting place near Edgware Road in London. The police had an informer; the plotters fell into a police trap. Thirteen were arrested, while one policeman, Richard Smithers, was killed. Five conspirators were executed, and five others were transported to Australia.

How widespread the Cato Street conspiracy was is uncertain. It was a time of unrest; rumours abounded.[1] Malcolm Chase noted that "the London-Irish community and a number of trade societies, notably shoemakers, were prepared to lend support, while unrest and awareness of a planned rising were widespread in the industrial north and on Clydeside."[2]

Origins[edit]

The conspirators were called the Spencean Philanthropists, a group taking their name from the British radical speaker Thomas Spence. The group was known for being a revolutionary organisation, involved in unrest and propaganda and plotting the overthrow of the government.

Some of them, particularly Arthur Thistlewood, had been involved with the Spa Fields riots in 1816. Thistlewood came to dominate the group with George Edwards as his second in command. Edwards was a police spy. Most of the members were angered by the Six Acts and the Peterloo Massacre, as well as with the economic depression and political conditions of the time.

The conspirators planned to assassinate the cabinet which was supposed to be together at a dinner. They would then seize key buildings, overthrow the government and establish a "Committee of Public Safety" to oversee a radical revolution. According to the prosecution at their trial, they had intended to form a provisional government headquartered in the Mansion House.[3]

Governmental crisis[edit]

Hard economic times encouraged social unrest. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 further worsened the economy and saw the return of job-seeking veterans. King George III's death on 29 January 1820 created a new governmental crisis. In a meeting held on 22 February, George Edwards suggested that the group could exploit the political situation and kill all the cabinet ministers after invading a fabricated cabinet dinner at the home of Lord Harrowby, Lord President of the Council, armed with pistols and grenades. Edwards even provided funds to help arm the conspirators.[4]

Thistlewood thought the act would trigger a massive uprising against the government. James Ings, a coffeeshop keeper and former butcher, later announced that he would have decapitated all the cabinet members and taken two heads to exhibit on Westminster Bridge.[5] Thistlewood spent the next hours trying to recruit more men for the attack. Twenty-seven men joined the effort.[citation needed]

Discovery[edit]

When Jamaican-born William Davidson, who had worked for Lord Harrowby, went to find more details about the cabinet dinner, a servant in Lord Harrowby's house told him that his master was not at home. When Davidson told this to Thistlewood he refused to believe it and demanded that the operation commence at once. John Harrison rented a small house in Cato Street as the base of operations. Edwards kept the police fully informed. Some of the other members had suspected Edwards, but Thistlewood had made him his top aide.[citation needed]

Edwards had presented the idea with the full knowledge of the Home Office, which had also put the advertisement about the supposed dinner in The New Times. When he reported that his would-be-comrades would be ready to follow his suggestion, the Home Office decided to act.[citation needed]

Arrest[edit]

On 23 February, Richard Birnie, Bow Street magistrate, and George Ruthven, another police spy, went to wait at a public house on the other side of the street of the Cato Street building with twelve officers of the Bow Street Runners. Birnie and Ruthven waited for the afternoon because they had been promised reinforcements from the Coldstream Guards, under the command of Captain FitzClarence, an illegitimate son of the Duke of Clarence (later William IV). Thistlewood's group arrived during that time. At 7:30 pm, the Bow Street Runners decided to apprehend the conspirators themselves.[citation needed]

In the resulting brawl, Thistlewood killed Bow Street Runner Richard Smithers with a sword. Some conspirators surrendered peacefully, while others resisted forcefully. William Davidson was captured; Thistlewood, Robert Adams, John Brunt and John Harrison slipped out through the back window, but were arrested a few days later.[citation needed]

Charges[edit]

"1. Conspiring to devise plans to subvert the Constitution. 2. Conspiring to levy war, and subvert the Constitution. 3. Conspiring to murder divers of the Privy Council. 4. Providing arms to murder divers of the Privy Council. 5. Providing arms and ammunition to levy war and subvert the Constitution. 6. Conspiring to seize cannon, arms and ammunition to arm themselves, and to levy war and subvert the Constitution. 7. Conspiring to burn houses and barracks, and to provide combustibles for that purpose. 8. Preparing addresses, &c. containing incitements to the King's subjects to assist in levying war and subverting the Constitution. 9. Preparing an address to the King's subjects, containing therein that their tyrants were destroyed, &c., to incite them to assist in levying war, and in subverting the Constitution. 10. Assembling themselves with arms, with intent to murder divers of the Privy Council, and to levy war, and subvert the Constitution. 11. Levying war."[6]

Trial and executions[edit]

John Thomas Brunt (1782–1820);

William Davidson (1781–1820);

James Ings (1794–1820);

Arthur Thistlewood (1774–1820);

and, Richard Tidd (1773–1820).

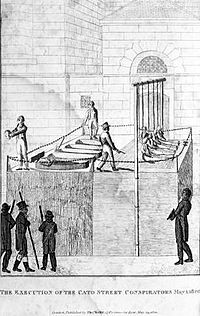

During the trial, the defence argued that the statement of Edwards, a government spy, was unreliable and he was therefore never called to testify. Police persuaded two of the men, Robert Adams and John Monument, to testify against other conspirators in exchange for dropped charges. On 28 April most of the accused were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered for high treason. All sentences were later commuted, at least in respect of this medieval form of execution, to hanging and beheading. The death sentences of Charles Cooper, Richard Bradburn, John Harrison, James Wilson and John Strange were commuted to transportation for life.[citation needed]

Arthur Thistlewood, Richard Tidd, James Ings, William Davidson and John Brunt were hanged at Newgate Prison on the morning of 1 May 1820 in front of a crowd of many thousands, some having paid as much as three guineas for a good vantage point from the windows of houses overlooking the scaffold.[7] Infantry were stationed nearby, out of sight of the crowd, two troops of Life Guards were present, and eight artillery pieces were deployed commanding the road at Blackfriars Bridge.[8] Large banners had been prepared with a painted order to disperse. These were to be displayed to the crowd if trouble caused the authorities to invoke the Riot Act.[7] However, the behaviour of the multitude was "peaceable in the extreme".[8]

The hangman was John Foxton.[9] After the bodies had hung for half an hour, they were lowered one at a time and an unidentified individual in a black mask decapitated them against an angled block with a small knife. Each beheading was accompanied by shouts, booing and hissing from the crowd and each head was displayed to the assembled spectators, declaring it to be the head of a traitor, before placing it in the coffin with the remainder of the body.[7]

Legacy[edit]

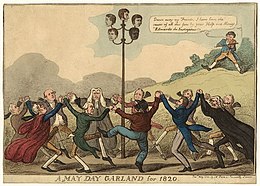

The British government used the incident to justify the Six Acts that had been passed two months before. However, in the House of Commons Matthew Wood MP accused the government of purposeful entrapment of the conspirators to smear the campaign for parliamentary reform. Although there is evidence that Edwards did incite certain actions of the conspirators, the idea is not supported by modern historians. However, the otherwise pro-government newspaper The Observer ignored the order of the Lord Chief Justice Sir Charles Abbott not to report the trial before the sentencing.[citation needed]

The treasonous plot is the subject of many books, as well as a play, Cato Street, written by the actor and author Robert Shaw, and a 2019 Edinburgh Fringe show, Cato Street 1820, written and performed by David Benson. The conspiracy was also the basis for a 1976 BBC Radio 4 drama 'Thistlewood' by Stewart Conn and 2001 radio drama, Betrayal: The Trial of William Davidson, by Tanika Gupta.[citation needed]

1A Cato Street was listed in 1974 for its association with the conspiracy.[10] The Greater London Council unveiled a blue plaque on the building in 1977.[11]

Historiography[edit]

Historian Caitlin Kitchener has used the theoretical framework of wound culture to examine the visual culture that was produced as a response to the incident. This included prints, newspaper illustrations and other publications.[12]

See also[edit]

- Assassination of Spencer Perceval

- Atlantic Revolutions

- Peterloo Massacre

- Radical War

- Radicalism (historical)

- Revolutions of 1820

- Six Acts

References[edit]

- ^ Elie Halevy, The Liberal Awakening 1815–1930 [A History of the English People In The Nineteenth Century – vol. II] (1949), pp. 80–84.

- ^ Malcolm Chase, "Thistlewood, Arthur (bap. 1774, d. 1820)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004).

- ^ Alan Smith, "Arthur Thistlewood: A 'Regency Republican'." History Today 3 (1953): 846–52.

- ^ E.g., in a letter delivered to Lord Harrowby on the day of execution, conspirator William Davidson stated that "Mr Edwards was the man who gave me the money to redeem the blunderbuss, which Adams carried away to Cato-street". Morning Chronicle, 2 May 1820, p. 3.

- ^ Gaunt, Richard A. (Spring 2019). "The Diabolical Cato-Street Plot: The Cato Street Conspiracy, 1820". Historian (141): 12–15.

- ^ Court decision. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey.

- ^ a b c "Execution of Thistlewood and Others for High Treason". The Morning Chronicle. No. 15915. London. 2 May 1820.

- ^ a b "Execution of Thistlewood, &c", The Times, 2 May 1820, p. 3. Accessed at The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ Clark, Richard, "A history of London's Newgate prison" at capitalpunishmentuk.org

- ^ "1A, CATO STREET W1, Non Civil Parish - 1066330 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Cato Street Conspiracy | Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ Kitchener, Caitlin (2023). "Cato Street Conspiracy and Consuming Crime: How Radical Politics Fed into the Public's Passion for Violent Media Coverage *". Parliamentary History. 42 (1): 51–74. doi:10.1111/1750-0206.12670. ISSN 0264-2824.

Further reading[edit]

- Chase, Malcolm. "Thistlewood, Arthur (bap. 1774, d. 1820)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004); online edn, September 2010. Accessed 12 September 2014.

- Craven, Miles. A Street Named Cato (2021)

- Gardner, John. Poetry and Popular Protest: Peterloo, Cato Street and the Queen Caroline Controversy (2011)

- Gatrell, Vic, Conspiracy on Cato Street: Liberty and Revolution in Regency London (2022)

- Johnson, D. Regency revolution: the case of Arthur Thistlewood (1975).

- Milsome, John. "Arthur Thistlewood and the Cato Street Conspiracy." Contemporary Review 217 (September 1970), pp. 151–54.

- Smith, Alan. "Arthur Thistlewood a Regency Republican," History Today (1953) 3#12, pp. 846–852.

- Stanhope, J. The Cato Street conspiracy (1962), the standard scholarly study

External links and other sources[edit]

- Original Documents from the Cato Street Conspiracy at the National Archives

- A Web of English History

- Black Presence in Britain about the conspiracy

- The text of the court decision

- Wilkinson, George Theodore An authentic history of the Cato-Street Conspiracy. Thomas Kelly, London, c. 1820

- Griffiths, Arthur The Chronicles of Newgate. Chapman and Hall, London 1884, Vol. II, pp. 278 et seq.

- Cato Street 1820 Stage production written and performed by David Benson