Erik Jarvik

Anders Erik Vilhelm Jarvik (30 November 1907 – 11 January 1998) was a Swedish paleontologist who worked extensively on the sarcopterygian (or lobe-finned) fish Eusthenopteron. In a career that spanned some 60 years, Jarvik produced some of the most detailed anatomical work on this fish, making it arguably the best known fossil vertebrate.

Jarvik was born at a farm in Utby Parish near Mariestad in northern Västergötland. He studied botany, zoology, geology, and paleontology at Uppsala University, where he took his licentiate's degree in 1937. In 1942, he completed his PhD with the dissertation On the structure of the snout of Crossopterygians and lower Gnathostomes in general. He participated in the Greenland expedition of Gunnar Säve-Söderbergh in 1932 and was appointed assistant in the Department of Palaeozoology of the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm in 1937; he eventually succeeded Erik Stensiö as professor and head of the department in 1960, retiring in 1972.

Research[edit]

Jarvik's research concerned mainly the sarcopterygian fishes. His main interests were in the so-called "rhipidistian" sarcopterygian fishes, which he held to be divided into two groups: the Osteolepiformes and the Porolepiformes.[1] He published several solidly descriptive works on Devonian sarcopterygians.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

After the death of Säve-Söderbergh, Jarvik was tasked with investigating and fully describing the anatomy of Ichthyostega. His work resulted in a 1996 monograph with an extensive photographic documentation of the material collected in 1929–1955.[11]

Work on Eusthenopteron[edit]

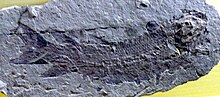

In particular, he conducted detailed anatomical studies of the cranium of Eusthenopteron foordi using a serial-section technique introduced by William Johnson Sollas and applied to fossil fishes by Erik Stensiö. A fossil of limited external quality was sectioned by grinding off a thin section, photographing the grind-off end and repeat the process until the whole fossil was worked through. The internal structures would then show up on long series of photographs. Working in the day before computer simulations, models were made by projecting reversal film on a board, and cut thin wax plates to match. The sticky wax plates could then be assembled to a three-dimensional scaled-up model of the skull, complete with internal structures such as nerve channels and other internal hollows rarely seen in fossils.[12][13][14] Further section to the cranium could easily be made by cutting the wax model at the desired angle. Due to the sticky nature of the wax used, a sectioned skull was put back together by simply pressing the two sections back together. This technique was also applied to the cranium of the porolepiform Glyptolepis groenlandica.[15]

Hypotheses on amphibian phylogeny[edit]

Jarvik was deeply involved in the debate over the principal structure and homology of the vertebrate head,[16][17][18] and he was responsible for a controversial proposal regarding the origin of the tetrapods. He proposed, on the basis of detailed analyses of the snout and nasal capsule structures as well as the intermandibular, neuroepiphysial, and occipital regions, that Tetrapoda was biphyletic. In his view, the anatomical details of the Caudata (salamanders) bound them to the primitive "porolepiform" fishes, while all other tetrapods (“eutetrapods”) – apodans possibly excepted – were descended from primitive osteolepiforms. Thus, in his view Amphibia had arisen twice.[19][20]

On the basis of his findings, he argued that Amphibia should be split, with salamanders (and possibly caecilians) in one class (the Urodelomorpha), and the frogs as a separate class, the Batrachomorpha. The Lepospondyli were considered to be possible urodelomorphans, while the "labyrinthodonts" were thought to be batrachomorphs. Jarvik's ideas was never widely accepted, though Friedrich von Huene did include his system in systematic treatment of tetrapods.[21] Few other supported his ideas, and today it has been abandoned by vertebrate paleontologists. The term "Batrachomorpha" is still occasionally used in a cladistic sense to denote labyrinthodonts more closely related to modern amphibians than to amniotes.

Lungfish phylogeny[edit]

Jarvik also studied the anatomy and relationships of lungfish[22] which he held to be relatively primitive gnathostomes, possibly related to holocephalans, and of acanthodians,[23] which he considered to be elasmobranchs rather than osteichthyans. He made contributions to a number of classical problems in comparative anatomy, including the origin of the vertebrates [24] the origin of the pectoral and pelvic girdles and paired fins,[25] and the homologies of the frontal and parietal bones in fishes and tetrapods[26]

Legacy[edit]

Some of Jarvik's views did not accord with general opinion in vertebrate paleontology.[27][28][29] However, his anatomical studies of Eusthenopteron foordi laid the foundations for modern studies of the transition from fishes to tetrapods. Jarvik was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and French Academy of Sciences and Knight of the Order of Vasa. The lungfish Jarvikia[30] and the osteolepiform Jarvikina[31] are named after him.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1942). On the structure of the snout of crossopterygians and lower gnathostomes in general. Zoologiska Bidrag från Uppsala, 21, 235-675.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1937). On the species of Eusthenopteron found in Russia and the Baltic states. Bulletin of the Geological Institution of the University of Upsala, 27, 63-127.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1944). On the exoskeletal shoulder-girdle of teleostomian fishes, with special reference to Eusthenopteron foordi Whiteaves. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, (3)21(7), 1-32.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1948). On the morphology and taxonomy of the Middle Devonian osteolepid fishes of Scotland. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, 3(25), 1-301.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1949). On the Middle Devonian crossopterygians from the Hornelen Field in Western Norway. Årbok Univ. Bergen, 1948, 1-48.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1950). Middle Devonian vertebrates from Canning Land and Wegeners Halvö (East Greenland). II. Crossopterygii. Meddelelser om Gr¢nland, 96(4), 1-132.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1950). Note on Middle Devonian crossopterygians from the eastern part of Gauss Halvö, East Greenland. With an appendix: An attempt at a correlation of the Upper Old Red Sandstone of East Greenland with the marine sequence. Meddelelser om Gr¢nland, 149(6), 1-20.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1950). On some osteolepiform crossopterygians from the Upper Old Red Sandstone of Scotland. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, (4)2, 1-35.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1967). On the structure of the lower jaw in dipnoans: with a description of an early Devonian dipnoan from Canada, Melanognathus canadensis gen. et sp. nov. In: Fossil vertebrates (eds. C. Patterson & P. H. Greenwood), Journal of the Linnean Society (Zoology), 47, 155-183.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1985). Devonian osteolepiform fishes from East Greenland. Meddelelser om Gr¢nland, Geoscience 13, 1-52.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1996). The Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega. Fossils and Strata, 40, 1-213.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1942). On the structure of the snout of crossopterygians and lower gnathostomes in general. Zoologiska Bidrag från Uppsala, 21, 235-675.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1954). On the visceral skeleton in Eusthenopteron with a discussion of the parasphenoid and palatoquadrate in fishes. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, (4)5, 1-104.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1975). On the saccus endolymphaticus and adjacent structures in osteolepiforms, anurans and urodeles. Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 218, 191-211.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1972). Middle and Upper Devonian Porolepiformes from East Greenland with special reference to Glyptolepis groenlandica n. sp. Meddelelser om Gr¢nland, 187(2), 1-295.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1960). Théories de l'évolution des vertébrés reconsidérées à la lumière des récentes découvertes sur les vertébrés inférieurs. Paris: Masson.

- ^ Bjerring, H. C. (1977). A contribution to structural analysis of the head of craniate animals. The orbit and its contents in 20-22 mm embryos of the North American actinopterygian Amia calva L., with particular reference to the evolutionary significance of an aberrant, nonocular, orbital muscle innervated by the oculomotor nerve and notes on the metameric character of the head in craniates. Zoologica Scripta, 6, 127–183.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1980). Basic structure and evolution of vertebrates. Vol. 1. London: Academic Press.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1980). Basic structure and evolution of vertebrates. Vol. 2. London: Academic Press.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1986). On the origin of the Amphibia. In: Studies in Herpetology (ed. Z. Roček), 1-24. Prague: Charles University.

- ^ Baron von Huen, F. (1946): Classification and Phylogeny of the Tetrapods. Geological Magazine No 86: pp 189-195. Cambridge University Press summary from Cambridge Journals

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1968). The systematic position of the Dipnoi. In: Current Problems of Lower Vertebrate Phylogeny (ed. T. Ørvig), Nobel Symposium 4, 223-245. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1977). The systematic position of acanthodian fishes. In: Problems in vertebrate evolution (eds. S. M. Andrews, R. S. Miles & A. D. Walker), 199-225. London: Academic Press.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1988). The early vertebrates and their forerunners. In: L'évolution dans sa réalité et ses diverses modalités, 35-64. Paris: Masson.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1965). On the origin of girdles and paired fins. Israel Journal of Zoology, 14, 141-172.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1967). The homologies of frontal and parietal bones in fishes and tetrapods. Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 163, 181-213.

- ^ Panchen, A. (1981). A Devonian view of vertebrate evolution. Nature, 292, 565-566.

- ^ Jarvik, E. (1981). [Review of:] Lungfishes, Tetrapods, Paleontology, and Plesiomorphy. Systematic Zoology, 30, 378-384.

- ^ Janvier, P. (1998). Erik Jarvik (1907-1998). Palaeontologist renowned for his work on the "four-legged fish." Nature, 392, 338.

- ^ Lehman, J.-P. (1959). Le Dipneustes du Devonien supérieur du Groenland. Meddelelser om Gr¢nland, 164, 1-58.

- ^ Vorobyeva, E. (1977). Morphology and nature of evolution of crossopterygian fish. Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta an SSSR, Akademia Nauk SSSR, 163, 1-239.

Selected publications[edit]

Books[edit]

- Théories de l'évolution des vertébrés reconsidérées à la lumière des récentes découvertes sur les vertébrés inférieurs. Masson, Paris. 1960.

- Basic Structure and Evolution of Vertebrates, 2 Vols. Academic Press, London. 1980