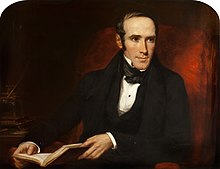

Andrew Combe

Andrew Combe | |

|---|---|

Andrew Combe | |

| Born | 27 October 1797 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 9 August 1847 (aged 49) Gorgie, Scotland |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Known for | Phrenology |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physiology |

Andrew Combe (27 October 1797 – 9 August 1847) was a Scottish physician and phrenologist.

Life[edit]

Combe was born in Edinburgh on 27 October 1797, the son of Marion (née Newton) and George Combe (1745–1816), a brewer, and was a younger brother of George Combe.[1] After some years at the Royal High School, he became a surgeon's pupil in 1812, residing during most of the time with his elder brother George Combe, and obtaining his diploma at Surgeons' Hall on 2 February 1817.[2]

In October 1817, he went to Paris to complete his medical studies, specialising in anatomy and investigating cerebral morphology under Spurzheim's supervision in 1818–19. After a visit to Switzerland, he returned to Edinburgh in 1819, intending to start a practice there. However, illness compelled him to spend the next two winters in the south of France and Italy. In 1823, he began to practise in Edinburgh. He had already made contributions to the newly established Edinburgh Phrenological Society. The first to be published was On the Effects of Injuries of the Brain upon the Manifestations of the Mind, read on 9 January 1823. In the same year he also answered Dr Barclay's attack on phrenology in his Life and Organisation. Combe's essay was so clearly written that a subsequent opponent of phrenology alluded to its "satanic logic".[2]

In 1823, Combe joined his brother and others in establishing the Phrenological Journal, following a debate at the Royal Medical Society in which he felt he had scored a major victory over the opponents of phrenology, but of which the Society declined to publish any account. This memorable discussion, inspired by one of Andrew Combe's essays, took place at the Royal Medical Society on 21 and 25 November 1823, and lasted till nearly four in the morning. The essay was published in the Phrenological Journal (vol 1, p. 337); but records of the discussion were suppressed by means of an injunction obtained by the Medical Society from the Court of Session. In 1825, Combe graduated with an MD at Edinburgh. His practice grew quickly because of Combe's personal qualities – his ability to listen, and his exceptional professional courtesy. In 1827, he was elected President of the Edinburgh Phrenological Society.[2]

Combe had been consulted in many cases of insanity and nervous disease, and on 6 February 1830 wrote an article in The Scotsman commenting unfavourably on the verdict of the jury in the Davies case in 1829. The doctors who had declared Davies insane were proved by the event to be quite right. Encouraged by this success, in 1831, Combe published his Observations on Mental Derangement, which was very successful.[2]

Ill health forced Combe to spend the winter of 1831–2 abroad, but he recovered sufficiently to begin writing his work on Physiology applied to Health and Education. This was published in 1834 and was a bestseller.[2]

In the early 1830s Combe's address is listed as 25 Northumberland Street in the fashionable New Town of Edinburgh. His brother George Combe is listed as living at the same address.[3] The house was purchased from John Gibson Lockhart (Sir Walter Scott's biographer and son-in-law) in 1825.

In 1834, Combe applied for the post of superintendent of the Montrose asylum – the first publicly funded post in mental hospital practice in Scotland – but, on receiving a request for a reference from William A. F. Browne – Combe withdrew his application and warmly endorsed his former student. Browne was successful in his application, and was celebrated at Montrose as an outstanding superintendent. However, in his influential lectures on asylum management, delivered in the Autumn of 1836, Browne did not mention phrenological thinking, and Combe had to await a delayed expression of gratitude in the dedication of Browne's lectures – What Asylums Were, Are, and Ought to Be – which were published to international acclaim in 1837.

Combe's health permitted him to resume practice to only a limited extent in 1833-5. Early in 1836 he received the appointment of physician to King Leopold I of Belgium (with Dr James Clark's recommendation) and moved to Brussels; but his health again failed, and he returned to Edinburgh in the same year. He soon completed and published his Physiology of Digestion (1836), which reached a ninth edition in 1849. A considerable practice now absorbed his energies, and in 1838 he was appointed a physician to Queen Victoria. In 1840, he published his last, and he considered his best book, The Physiological and Moral Management of Infancy. The sixth edition appeared in 1847.

During his later years, tuberculosis made serious advances. Two winters in Madeira and a voyage to the United States failed to improve things, and he died while on a visit to a nephew at Gorgie Mills, on the south-west side of Edinburgh, on 9 August 1847.[2]

Combe never married. He is buried with his grandfather, George Combe, brewer (d. 1816) in St Cuthberts Churchyard. The grave is located on the south side of the "Bairn's Knowe" behind the older stones, and backing onto the former church halls.

His biography, written by his brother, was published in 1850.[2]

Criticism of vegetarianism[edit]

Combe criticised vegetarianism and the dieting ideas of William Alcott and Sylvester Graham. In his book The Physiology of Digestion he commented that "the arguments of Mr Graham and Dr Alcott in favour of exclusive vegetable diet, are not based on sound physiological principles, and the broad assertions which they make of the superior strength of vegetable-eating savages in comparison with civilised Europeans, rest on insufficient evidence, and are not supported by the experience of trustworthy observers."[4]

Combe denied that Isaac Newton was a strict vegetarian and noted that "he did not usually confine himself to a vegetable diet."[5]

Selected publications[edit]

- The Principles of Physiology Applied to the Preservation of Health (1839)

- The Universal Guide to Health (1849)

- The Physiology of Digestion, Considered with Relation to the Principles of Dietetics (with James Coxe, 1860)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jacyna, L. S. "Combe, Andrew (1797–1847)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6017. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g Bettany 1887.

- ^ "(75) - Scottish Post Office Directories > Towns > Edinburgh > 1805-1834 - Post Office annual directory > 1832-1833 - Scottish Directories". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Combe, Andrew. (1860). The Physiology of Digestion. Edinburgh: Maclachan & Stewart. pp. 145-146

- ^ Lawrence, Christopher; Shapin, Steven. (1998). Science Incarnate: Historical Embodiments of Natural Knowledge. University of Chicago Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-226-47012-1

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bettany, George Thomas (1887). "Combe, Andrew". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 11. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 425–426.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bettany, George Thomas (1887). "Combe, Andrew". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 11. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 425–426.

- 1797 births

- 1847 deaths

- British academic journal editors

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- Critics of vegetarianism

- Dietitians

- Mental health professionals

- People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh

- Medical doctors from Edinburgh

- Phrenologists

- Scottish anatomists

- Scottish medical writers

- Scottish physiologists

- University of Paris alumni

- British expatriates in France